The start of a new school year and the increase in children getting COVID-19 due to the highly contagious delta variant has parents worried about their kids’ health. They’re also wondering, why is it taking so long to produce a vaccine for children under 12 years of age.

The concern grows as do the latest case numbers. COVID cases involving young children have “increased exponentially” to levels the U.S. hasn’t seen since last winter, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. The latest statistics show child infections made up almost a quarter of the reported cases for the week ending August 26.

It was thought that we would have a vaccine option for younger kids by now. What is taking so long?

For one thing, despite having tens of millions of U.S. adults showing that the vaccines are safe and effective, scientists like Dr. Kari Simonsen, who is leading the trial of the Pfizer vaccine at Children’s Hospital & Medical Center in Omaha, say it’s not enough to just rely on research gathered for grownups.

“We can’t make assumptions about the safety or tolerability of medicines in children being the same as for adults.”

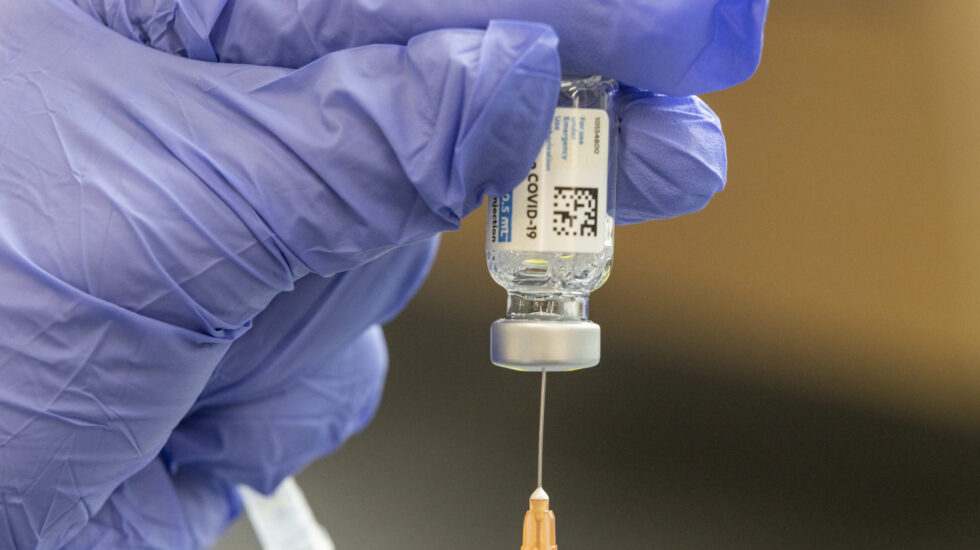

For another, clinical trial data is still being collected on the proposed COVID-19 vaccines for younger children. Once the companies producing the vaccines collect the trial results, they still have to submit the information to the FDA for assessment and eventual authorization. Emergency authorizations by the agency can take several weeks.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA commissioner who is now a board member of Pfizer, told CBS’ Face the Nation on Sunday the vaccine maker expects to ask the agency for authorization “at some point in September” and then file the application for an emergency use of the vaccine “potentially as early as October.”

Gottlieb added that it would “put us on a time frame where the vaccines could be available at some point late fall, more likely early winter depending on how long FDA takes to review the application.”

From CNN:

For the kid's version of the Covid-19 vaccine, scientists use results from the adult trials and a full pediatric trial.Having the adult research speeds up the process. For people as young as 12, Perlman explains, the companies didn't have to enroll the 30,000 people it needed for adult trials because it could do what's called "immunobridging." The data showed that for this age group, the immune response was the equivalent of adults'. Companies take a similar approach with the younger kids, but in early August, the FDA asked for six months of follow-up safety data, instead of the two months it asked for with adults. It also asked Pfizer and Moderna to double the number of children ages 5 to 11 in clinical trials.